The Quiet Revolution Against Optimization Culture

How a new generation is rediscovering what we lost on the way to the future

By S. Falken

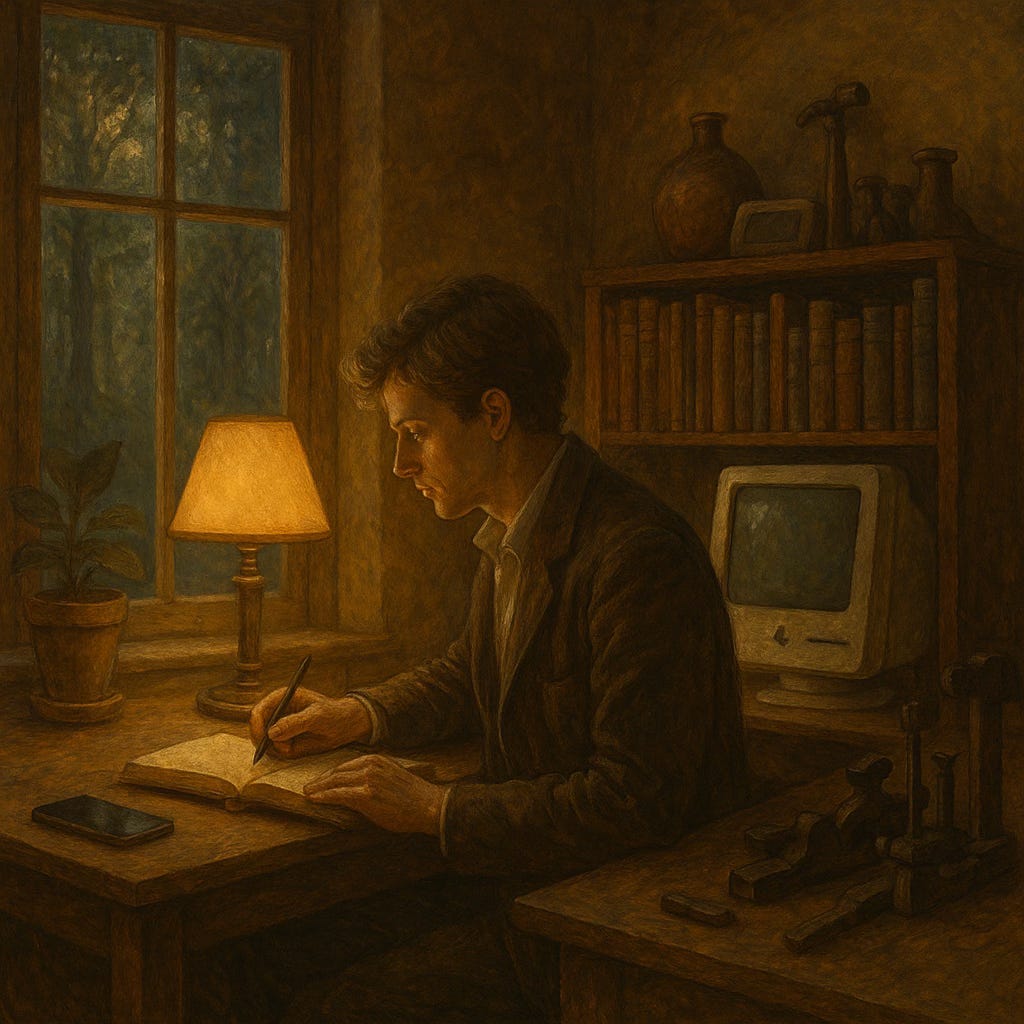

In a San Francisco loft last autumn, two dozen people gathered around a long wooden table. There were practically no phones in sight. No laptops on the table. Instead, there were books, handwritten notes, and—most notably—focused conversation. This wasn't a digital detox retreat or a mindfulness workshop. It was a meeting of what participants half-jokingly call "the resistance."

These weren't luddites. Among them were former tech executives, designers, artists, educators, and philosophers. Many had helped build the very systems they now questioned. What united them wasn't a rejection of technology but a growing concern about what our optimization-obsessed culture had subtly taken from us—what we might call the unquantifiable dimensions of human experience.

"We didn't gather to burn our smartphones," says Elena Markova, a former product designer at one of Silicon Valley's most prominent companies. "We came together to ask: What happens when efficiency becomes an end in itself? When optimization becomes the water we swim in, so ubiquitous we no longer notice its effects?"

This gathering represented just one node in a quietly growing network of people who identify with what some are calling "Neo-Romantic Realism"—a philosophical stance that's gaining traction not as an organized movement but as a recognition that something vital is being overlooked in our rush toward frictionless efficiency.

The Premise: Something Missing in Modern Life

In conversations with dozens of these neo-romantics, a common sentiment emerges: There is something deeply off in the texture of daily life. We feel it in the blur of days, the flattening of self, the vanishing of time for anything that doesn't scale. The systems around us are optimized. Our tools are powerful. Yet many of us feel scattered, distracted, disembodied, and quietly aching for something we can't name.

The statistics bear this out. Despite unprecedented technological advancement, rates of depression, anxiety, and loneliness continue to rise. Something about our optimized world isn't working for human flourishing.

"What we're missing isn't another app or platform," explains Dr. Jonathan Wei, a cognitive scientist studying attention. "It's a recognition that human experience isn't meant to be optimized. It's meant to be lived in all its messy, inefficient glory."

This isn't simple nostalgia. The neo-romantics aren't calling for a return to some idealized past. Rather, they're suggesting a selective recovery of what was valuable but discarded in our race toward the future.

A Philosophy with Historical Echoes

The term "Neo-Romantic Realism" might sound academic, but its components are clarifying:

The "Neo" acknowledges its historical awareness—this isn't the first time humans have responded to technological revolution with a renewed emphasis on subjective experience. The original Romantics emerged as a response to the Industrial Revolution, championing emotion and individualism against mechanistic rationality.

The "Romantic" element asserts that beauty, feeling, mystery, and meaning aren't optional luxuries but essential dimensions of a full human life—dimensions that often elude optimization metrics.

And the "Realism" signals that this isn't a retreat into fantasy. Proponents aren't abandoning technology or progress. They're simply asking: progress toward what? And at what cost?

"We're not anti-technology," says Marcus Chen, who left a senior position at a major tech company to start a design firm focused on what he calls "humane technology." "We're pro-human. And sometimes being pro-human means questioning whether efficiency should always be the highest value."

The Rejection of Total Optimization

What neo-romantics specifically reject is what philosopher Amelia Rodriguez calls "the ideology of total optimization"—the belief that everything in life should be frictionless, measurable, scalable, and efficient.

This ideology has become so pervasive that we barely notice its assumptions: that human value is primarily economic, that time is a productivity slot, that beauty is an afterthought, that attention is a commodity, that the self is a brand.

"The problem isn't optimization itself," says Rodriguez. "It's when optimization becomes totalizing—when we can no longer imagine alternatives to seeing the world through its lens."

Consider how we've come to talk about our lives: we "optimize" our sleep, "hack" our productivity, seek "efficient" relationships, and "maximize" our leisure. Even our resistance to optimization is often framed as a way to optimize creativity or wellbeing.

The neo-romantics are suggesting something more radical: What if some experiences aren't meant to be optimized at all? What if some values exist outside the optimization framework entirely?

Reaffirming the Unquantifiable

At its core, Neo-Romantic Realism reaffirms what many of us intuitively know but increasingly struggle to defend: Not all that matters can be monetized. Not all that is valuable can be measured. Not all that is true can be proven. Not all that is human should be automated.

This philosophical stance values what economist Jaume Casals calls "the dignity of unoptimized experience": a walk without tracking steps, a conversation without an agenda, reading without counting pages, creating without concern for likes or shares.

"The body isn't a liability to be overcome," says Dr. Maya Williams, a neurobiologist studying embodied cognition. "The analog isn't a limitation to be transcended. Sometimes limits aren't constraints on freedom but the very form freedom takes."

This perspective isn't anti-progress. It's simply a recalibration of what progress means—and who it serves.

What This Looks Like in Practice

What makes Neo-Romantic Realism particularly interesting is how it's manifesting in practical ways across disciplines.

In technology, we're seeing the emergence of what some call "slow tech"—tools designed not to maximize engagement but to respect attention and enhance human capability without creating dependency.

In education, there's growing interest in what educator Paulo Mendes calls "deep learning"—approaches that prioritize wisdom and understanding over information processing and testable outcomes.

In urban planning, architects like Sophia Lee are designing what she calls "human-scale spaces"—environments that encourage serendipitous interaction and connection rather than frictionless efficiency.

In arts and culture, there's renewed interest in works that resist easy consumption—complex novels, challenging films, music that rewards repeated listening rather than algorithmic optimization.

Even in business, companies are beginning to question metrics-obsessed management. "We spent years optimizing for employee efficiency," says James Harrington, CEO of a mid-sized tech company. "Then we realized we were optimizing away the very things that made people want to work here—creativity, connection, meaning."

These aren't isolated trends. They represent a broader cultural shift—a quiet revolution against the assumption that optimization should be the default orientation toward every aspect of life.

Not a Movement but a Recognition

What makes this shift difficult to track is that it isn't organizing as a traditional movement. There's no central leadership, no manifesto, no formal membership. It's emerging organically as individuals across disciplines recognize the same pattern and respond to it in their own contexts.

"It's more like a widespread awakening than a coordinated effort," says cultural critic Leila Washington. "People in different fields are independently coming to similar conclusions about the limitations of optimization culture."

This lack of centralization may actually be its strength. Rather than becoming another brand or identity to be commodified, Neo-Romantic Realism functions more as a recognition—a name for something many people have been feeling but struggling to articulate.

"Once you name it, you see it everywhere," says Washington. "And once you see it, you can't unsee it."

The Deeper Question: Technology for What?

At its philosophical core, Neo-Romantic Realism asks a deceptively simple question: What is technology for?

Is it merely to make things faster, more efficient, more scalable? Or is it to enhance human flourishing in all its dimensions—including those that resist measurement?

"We've designed our systems as if the highest goal is to optimize away friction," says ethicist Dr. Robert Kim. "But what if some forms of friction—contemplation, difficulty, limitation—are essential to what makes life meaningful?"

This question becomes increasingly urgent as artificial intelligence advances. When we can automate more aspects of human experience, we're forced to confront what we value about being human beyond efficiency.

"The rise of AI doesn't make Neo-Romantic Realism obsolete—it makes it essential," argues technology theorist Maria Gonzalez. "As machines become better at optimization, humans need to become better at articulating what lies beyond optimization."

Looking Forward: The Next 50 Years

If the trend continues, historians may look back on this period as a pivotal moment—when we began to question whether optimization should be our default orientation toward life.

This wouldn't mean abandoning technological progress. Rather, it would mean directing that progress toward ends that serve human flourishing in its fullest sense—not just efficiency, convenience, and scale, but also meaning, connection, beauty, and depth.

The neo-romantics aren't calling for a return to some pre-technological Eden. They're calling for a more nuanced relationship with technology—one that recognizes both its potential to enhance human capability and its tendency to flatten human experience when left unquestioned.

"The real question isn't whether technology is good or bad," says Markova. "It's whether we're designing technology to serve our highest values or whether we're reshaping our values to conform to what technology can measure and optimize."

In this sense, Neo-Romantic Realism represents not a rejection of the future but a more humanistic vision of what that future might be—one where technology serves human flourishing rather than narrowing it.

As we look toward the next half-century of technological development, this reorientation may prove to be not just philosophically satisfying but practically necessary. In a world of increasing automation, the most valuable human qualities will be precisely those that resist optimization—creativity, wisdom, empathy, meaning-making.

The neo-romantics are suggesting that these qualities aren't luxuries we can afford to lose. They're the essence of what makes human experience valuable in the first place.

"We don't need another revolution," says Chen. "We need a restoration. Not of the past, but of what was lost on the way to the future."

That restoration is already quietly underway. And fifty years from now, we may look back on it as the moment when we remembered that technology was meant to serve humanity—not the other way around.