Whatever Happened to Memory?

The quiet disappearance of a classic children’s game—and what it reveals about how we train minds in the age of distraction.

By D Lightman

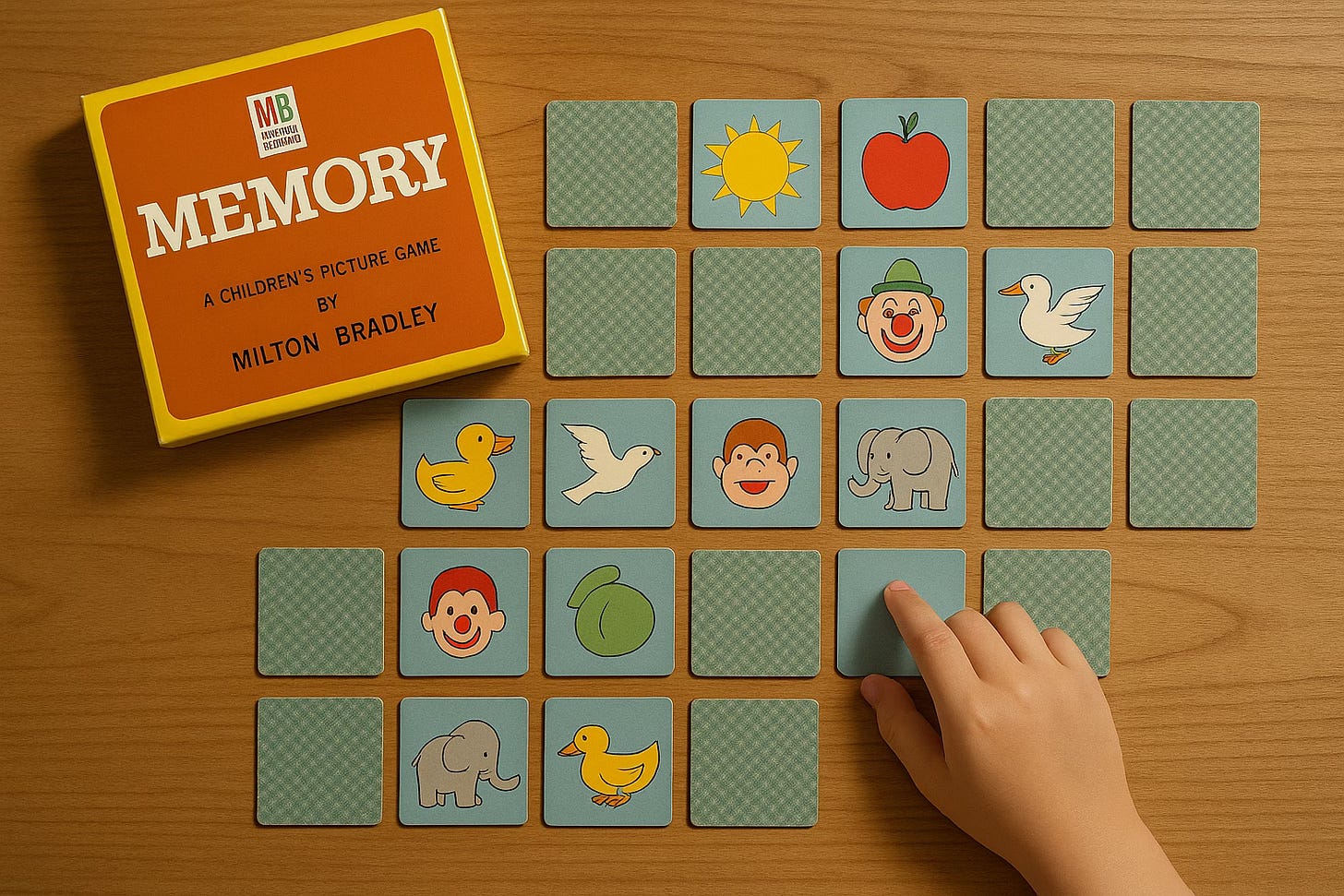

You flip a card. A duck. You flip another. A sun. No match. You try to remember. That’s the game.

It’s hard to overstate just how elemental Memory—Milton Bradley’s card-flipping classic—once was. A staple of childhood in the 70s, 80s, and even 90s, it required no batteries, no narrative arc, no flashy characters. Just a grid of squares, a good table, and your brain. The goal was as humble as it was profound: remember where things are. It was almost meditative.

And now? Who plays Memory anymore?

Sure, you can still find it, buried on page four of an Amazon search or in the corner of a preschool classroom whose funding hasn’t been slashed. But it’s no longer in the cultural bloodstream. Ask a ten-year-old today what “Memory” is, and they’re more likely to show you an iPad photo widget or a TikTok slideshow than a grid of foxes and balloons.

It’s not just nostalgia speaking. Memory was, in retrospect, one of the few games that rewarded deep attention. It cultivated something we’ve become starved for: the slow build of inner mapping. It asked children not to guess, not to mash buttons, not to wait for dopamine drops—but to notice, to retain, and to try again.

The disappearance of Memory isn’t tragic because of the game itself—it’s tragic because of what its decline symbolizes. In a world where even toddlers are digital natives, training for the swipes and scrolls of modern life, we’ve lost sight of how foundational focused recall used to be. We don’t train attention now; we monetize it. We don’t sharpen memory; we outsource it.

Is this just the cranky drift of an aging generation? Possibly. But maybe it’s also a signal worth decoding. Maybe Memorywas never just a game. Maybe it was a quiet kind of scaffolding we didn’t realize we were standing on—until we replaced it with pixels and forgot what remembering felt like.